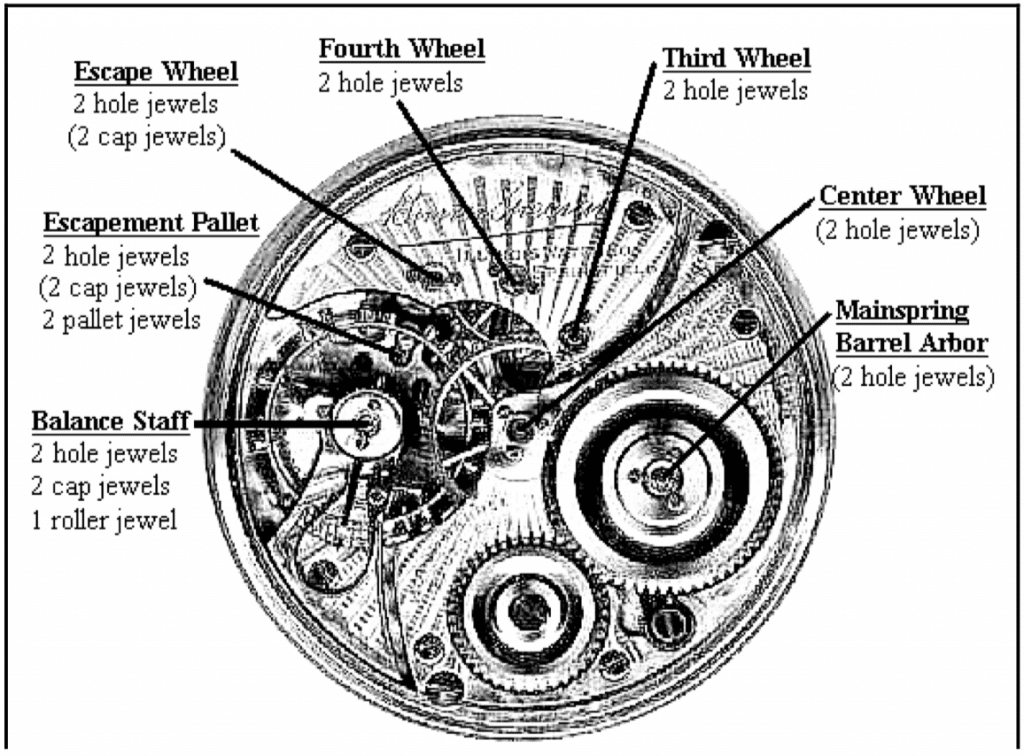

A watch movement mostly consists of a number of gears [called “wheels”] held in place by an upper and a lower plate. Each wheel has a central shaft [called an “arbor”] running through it, the ends of which fit into holes in the plates. If you have a metal shaft in a metal hole, with nothing to protect it, it will eventually wear away as the shaft turns. To prevent wear, and also to reduce friction, most watches have tiny doughnut-shaped jewels at the ends of many of the wheel arbors to keep them from coming into direct contact with the edges of the hole. The jewels are usually natural or man-made rubies, but can also be diamonds and sapphires. The fastest moving wheels [especially the balance wheel] on a watch frequently have additional “cap” jewels on top of the regular “hole” jewels to prevent the arbor from moving up and down, and most watches also have a few special jewels [called “pallet” and “roller” jewels] as part of the escapement.

Very early pocket watches rarely had jewels, simply because the concept hadn’t been invented yet or wasn’t in common use. By the mid 1800’s, watches typically had 6-10 jewels, and a watch with 15 jewels was considered high grade.

By the 20 th century, however, more and more watches were being made with higher jewel counts, and the quality of a watch is often judged by how many jewels it has. Thus, lower grade American-made watches from the late 1800’s and into the 1900’s typically have jewels only on the balance wheel and the escapement [7 jewels total]. Medium grade watches have 11-17 jewels, and high grade watches usually have 19-21 jewels. Extremely complicated watches, such as chronometers, chronographs, calendar and chiming watches, might have upwards of 32 jewels, and some high grade railroad watches have “cap” jewels on the slower wheels in addition to the faster moving wheels.

Note that, although the number of jewels that a watch has is usually a good indication as to its overall quality, this is not an absolute standard for three main reasons. First, as mentioned above, many watches made prior to the 20 th century were considered to be “high grade” for their day, in spite of the fact that they only have 15 jewels. Second, some watches have extra jewels that were added primarily for show and which did not add to the watch’s accuracy or quality [and which were sometimes not

even real jewels to begin with!] Third, there has been significant debate over the years as to how many jewels a watch even needs to be considered “high grade.” Webb C. Ball, the man most responsible for setting the standards by which railroad watches were judged in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, claimed that anything beyond 17 or 19 jewels was not only unnecessary, but actually made a watch more difficult to maintain and repair. The more common notion of “the more jewels the better” is not likely to go away anytime soon, however.

Most pocket watches made in the late 1800’s and thereafter that have more than 15 jewels have the jewel count marked directly on the movement. If there is no jewel count marked, and the only visible jewels are the ones on the balance staff [right in the center of the balance wheel], the watch probably only has 7 jewels. Note that a watch with 11 jewels looks identical to one with 15 jewels, since the extra 4 jewels are on the side of the movement directly under the dial. Also, a 17 jewel watch looks the same as a 21 jewel watch to the naked eye, since the additional jewels in this case are usually all cap jewels at the top and bottom of two of the wheels.

Location of the jewels on a 16 size, 23 jewel Illinois “Bunn Special.” Jewels in parentheses are typically found only on higher grade watches. The exact arrangement of jewels varied from company to company.